Daljit

Ami

Revisiting

Sadayat Hasan Manto (1912-1955) on his birth centenary turned out to

be an experience which cannot be described by a single adjective. It

was not just a return to Manto but also a home-coming to my

associations with him. I was introduced to Manto in the 1980s during

my graduation in A S College Khanna, in Ludhiana district of Punjab.

There, I could immediately relate Manto’s Toba

Tek Singh, as

the prevalent vicious communal atmosphere and brutal state response

was nothing short of insanity. After graduation I came to Chandigarh

which, despite being the capital of Punjab was aloof from the madness

reigning in the countryside. Here, Manto again helped me to

understand how the same situation could have different impacts. The

massacre of April 1919 of Jalianwala Bagh, Amritsar had changed the

life of Udham Singh and Sadayat Hasan Manto in different directions.

Udham Singh became part of history as Ram Mohammad Singh Azad when he

avenged the massacre of Jalianwala Bagh and was hung by the British.

In another but equally powerful trajectory, Manto wrote his first

short story, Tamasha,

using the backdrop of the Jalianwala Bagh massacre, and went on to

become one of the most acclaimed story tellers of the Subcontinent,

with prolific writing until his untimely death at forty two.

Revisiting

Sadayat Hasan Manto (1912-1955) on his birth centenary turned out to

be an experience which cannot be described by a single adjective. It

was not just a return to Manto but also a home-coming to my

associations with him. I was introduced to Manto in the 1980s during

my graduation in A S College Khanna, in Ludhiana district of Punjab.

There, I could immediately relate Manto’s Toba

Tek Singh, as

the prevalent vicious communal atmosphere and brutal state response

was nothing short of insanity. After graduation I came to Chandigarh

which, despite being the capital of Punjab was aloof from the madness

reigning in the countryside. Here, Manto again helped me to

understand how the same situation could have different impacts. The

massacre of April 1919 of Jalianwala Bagh, Amritsar had changed the

life of Udham Singh and Sadayat Hasan Manto in different directions.

Udham Singh became part of history as Ram Mohammad Singh Azad when he

avenged the massacre of Jalianwala Bagh and was hung by the British.

In another but equally powerful trajectory, Manto wrote his first

short story, Tamasha,

using the backdrop of the Jalianwala Bagh massacre, and went on to

become one of the most acclaimed story tellers of the Subcontinent,

with prolific writing until his untimely death at forty two. In

Chandigarh I learnt that Manto belonged to Papraudi, a village near

Samrala in Ludhiana district. We Punjabis have a fluid definition of

the term ‘village’. Whenever a Bihari labourer received a

visitor, we used to say that someone had come to meet him from his

village. It did not matter that one was from Gopalganj at the western

end of Bihar and the other from Kotihar in the east. Similarly, when

we move out of our villages the concept of village expanded along

with the distance from native place. Living in Europe or North

America, someone from Bahawalpur (West Punjab) and other one from

Patiala (East Punjab) can comfortably claim that they belong to same

village. Manto’s village is just 15 km from my village, Daudpur —

in the same district and tehsil.

This piece of information made me feel closer to Sadayat Hasan Manto.

From a mere reader I became his garain or

someone from the same village.

In

Chandigarh I learnt that Manto belonged to Papraudi, a village near

Samrala in Ludhiana district. We Punjabis have a fluid definition of

the term ‘village’. Whenever a Bihari labourer received a

visitor, we used to say that someone had come to meet him from his

village. It did not matter that one was from Gopalganj at the western

end of Bihar and the other from Kotihar in the east. Similarly, when

we move out of our villages the concept of village expanded along

with the distance from native place. Living in Europe or North

America, someone from Bahawalpur (West Punjab) and other one from

Patiala (East Punjab) can comfortably claim that they belong to same

village. Manto’s village is just 15 km from my village, Daudpur —

in the same district and tehsil.

This piece of information made me feel closer to Sadayat Hasan Manto.

From a mere reader I became his garain or

someone from the same village. In

the 1990s Lal

Singh Dil,

a revolutionary Punjabi poet was running a roadside tea stall in

Samrala, from where I used to change my bus while commuting between

Chandigarh and Daudpur. Mostly, I used to stop at his tea stall

to talk about poetry, politics and literature or sometimes just to

chat. It was a great feeling that Manto, Dil and I are garain.

In

the 1990s Lal

Singh Dil,

a revolutionary Punjabi poet was running a roadside tea stall in

Samrala, from where I used to change my bus while commuting between

Chandigarh and Daudpur. Mostly, I used to stop at his tea stall

to talk about poetry, politics and literature or sometimes just to

chat. It was a great feeling that Manto, Dil and I are garain.

I went to Lahore in 2003 to attend the Punjabi World Conference. In a parallel program on the Seraiki language someone told me that Hamid Akhtar was also in the gathering. Hamid Akhtar was an old friend of Manto and Sahir Ludhianvi and his ancestral village was also in Ludhiana district. They all migrated to Pakistan after Partition but Sahir eventually returned to India. Hamid Akhtar was looking very frail, as he had just recovered from throat cancer. I was told that his hearing was very weak so he would not be able to understand many things and, furthermore, he could not speak very easily.

However, I

was sure that he could listen to his garain. I

touched his feet and greeted him with folded hands, “Sat Sri Akal.”

He looked at me and I introduced myself, “Mein Samrale toh ayan.”

(I have come from Samrala.) In a trice, Hamid was on his feet. He

hugged me and announced, without the help of a loudspeaker, “Eh

mere pindo aya. Manto de pindon.

(He has come from my village, from Manto’s village.)” He made me

sit next to him, all the while holding my hand. His first question:

“Samrale vich kithon

ayan.”

(From where in Samrala do you come?) I replied, “Daudpur.” With a

few explanations, he could understand the geography as well as roads

from Daudpur to Papraudi and to his native village near Jagraon.

Hamid subsequently recovered from cancer and has visited Chandigarh

twice, thereafter. He would call and ask, “Mein

aa gayan, sham nu tun meinu sharab pilauni aa.”

(I am here. In the evening you will take me for a drink.) We would

end up discussing Manto, Sahir, India and Pakistan. This isSadda

Gran, our

village.

However, I

was sure that he could listen to his garain. I

touched his feet and greeted him with folded hands, “Sat Sri Akal.”

He looked at me and I introduced myself, “Mein Samrale toh ayan.”

(I have come from Samrala.) In a trice, Hamid was on his feet. He

hugged me and announced, without the help of a loudspeaker, “Eh

mere pindo aya. Manto de pindon.

(He has come from my village, from Manto’s village.)” He made me

sit next to him, all the while holding my hand. His first question:

“Samrale vich kithon

ayan.”

(From where in Samrala do you come?) I replied, “Daudpur.” With a

few explanations, he could understand the geography as well as roads

from Daudpur to Papraudi and to his native village near Jagraon.

Hamid subsequently recovered from cancer and has visited Chandigarh

twice, thereafter. He would call and ask, “Mein

aa gayan, sham nu tun meinu sharab pilauni aa.”

(I am here. In the evening you will take me for a drink.) We would

end up discussing Manto, Sahir, India and Pakistan. This isSadda

Gran, our

village. Recently,

I visited Papraudi to make a special program for the news channel Day

and Night News, on Sadayat Hasan Manto’s birth centenary. One of

Manto’s contemporaries, Ujjagar Singh, remembers having played with

him when they were children. At the age of ninety plus Ujjagar Singh

has memories of Manto and his family. He identified Manto’s house,

which was auctioned after Partition by government as ‘evacuee

property’. I asked him if he had read Manto’s writing. He

replied, “I have not read him as I can’t read Urdu. I have heard

that he is a renowned writer. He has made our village proud.” I

talked to at least half a dozen people but none of them was familiar

with Manto’s writings.

Recently,

I visited Papraudi to make a special program for the news channel Day

and Night News, on Sadayat Hasan Manto’s birth centenary. One of

Manto’s contemporaries, Ujjagar Singh, remembers having played with

him when they were children. At the age of ninety plus Ujjagar Singh

has memories of Manto and his family. He identified Manto’s house,

which was auctioned after Partition by government as ‘evacuee

property’. I asked him if he had read Manto’s writing. He

replied, “I have not read him as I can’t read Urdu. I have heard

that he is a renowned writer. He has made our village proud.” I

talked to at least half a dozen people but none of them was familiar

with Manto’s writings. Then

we went to the village Gurudwara where the Punjabi Sahit Sabha,

Delhi, opened the Manto Memorial Library two years ago. The caretaker

of the Gurudwara, Lakhwinder Singh, looks after the library as it is

housed in his one room accommodation. The bookshelf carrying 200

books has two translated volumes of Manto’s stories. The library

attracts not more then a couple of readers a month so Lakhwinder

Singh has not felt the need to unbundle books. Now Punjabi Sahit

Sabha Delhi is planning to shift this collection to Samrala.

Hopefully Manto’s writings will have more readers in his home

village.

Then

we went to the village Gurudwara where the Punjabi Sahit Sabha,

Delhi, opened the Manto Memorial Library two years ago. The caretaker

of the Gurudwara, Lakhwinder Singh, looks after the library as it is

housed in his one room accommodation. The bookshelf carrying 200

books has two translated volumes of Manto’s stories. The library

attracts not more then a couple of readers a month so Lakhwinder

Singh has not felt the need to unbundle books. Now Punjabi Sahit

Sabha Delhi is planning to shift this collection to Samrala.

Hopefully Manto’s writings will have more readers in his home

village. Continuing

my quest for Manto the person, I went to Amritsar to film the places

he is supposed to have frequented. One such place is Katra Sher Singh

where he lived. The demography of this area has changed, as it was a

Muslim dominated locality before Partition, and witnessed remorseless

killings and brutality of untold magnitude. Katra Sher Singh now has

a Hindu-Sikh population. No trace of its bloody past or its displaced

populace is visible to an observer.

Continuing

my quest for Manto the person, I went to Amritsar to film the places

he is supposed to have frequented. One such place is Katra Sher Singh

where he lived. The demography of this area has changed, as it was a

Muslim dominated locality before Partition, and witnessed remorseless

killings and brutality of untold magnitude. Katra Sher Singh now has

a Hindu-Sikh population. No trace of its bloody past or its displaced

populace is visible to an observer. Manto

might have got his characters of Khol

Do and Thanda

Ghosht straight

out of these environs, I imagine as I walk the streets. Since I had

been steeped in Manto for many days, I could feel the traumatized

young Sakina’s presence. As in Khol

do,

she is not confined only to being Sirajudin’s daughter, but

symbolizes the vulnerability of women subjected to sexual violence

during Partition. Even after 65 years, it is scary. I do not want to

dwell on what Manto had gone through while witnessing and then

recording these details. He took refuge in Toba

Tek Singh’s Bishan

Singh, who says, “Aupar

di, gargar di, bedhiyana

Manto

might have got his characters of Khol

Do and Thanda

Ghosht straight

out of these environs, I imagine as I walk the streets. Since I had

been steeped in Manto for many days, I could feel the traumatized

young Sakina’s presence. As in Khol

do,

she is not confined only to being Sirajudin’s daughter, but

symbolizes the vulnerability of women subjected to sexual violence

during Partition. Even after 65 years, it is scary. I do not want to

dwell on what Manto had gone through while witnessing and then

recording these details. He took refuge in Toba

Tek Singh’s Bishan

Singh, who says, “Aupar

di, gargar di, bedhiyana di, annex di, mungi di daal of

the lantern of the Hindustan of the Pakistan government, dur

fiteh munh.”

All the words of this sentence are familiar but still it is an enigma

inviting silence. Manto too, is such an enigma who may have

grown out of words so he chose silence at the age of forty two. As

a garain of

Manto I am unnerved by his silence, Sakina’s predicament and Bishan

Singh’s gibberish. Oh, when Manto is not confined to any one

village, why should I think that I am the only one who is scared

while revisiting him? It leaves me with a final question: can scared

people celebrate birth centenaries?

di, annex di, mungi di daal of

the lantern of the Hindustan of the Pakistan government, dur

fiteh munh.”

All the words of this sentence are familiar but still it is an enigma

inviting silence. Manto too, is such an enigma who may have

grown out of words so he chose silence at the age of forty two. As

a garain of

Manto I am unnerved by his silence, Sakina’s predicament and Bishan

Singh’s gibberish. Oh, when Manto is not confined to any one

village, why should I think that I am the only one who is scared

while revisiting him? It leaves me with a final question: can scared

people celebrate birth centenaries?

ਏਥੇ ਸਆਦਤ ਹਸਨ ਮੰਟੋ ਦਫ਼ਨ ਏ। ਉਹਦੇ ਸੀਨੇ 'ਚ ਕਹਾਣੀ ਲਿਖਣ ਦੀ ਕਲਾ ਦੇ ਸਾਰੇ ਭੇਤ ਤੇ ਰਮਜ਼ਾਂ ਦਰਜ ਨੇ। ਉਹ ਹੁਣ ਵੀ ਮਣਾਂ ਮੂੰਹ ਮਿੱਟੀ ਹੇਠ ਦੱਬਿਆ ਸੋਚ ਰਿਹਾ ਏ ਕਿ ਉਹ ਵੱਡਾ ਕਹਾਣੀਕਾਰ ਏ ਜਾਂ ਰੱਬ।

(ਸਦਾਅਤ ਹਸਨ ਮੰਟੋ ਨੇ ਆਪਣ ਕਤਬਾ ਲਿਖ ਕੇ 18 ਅਗਸਤ 1954 ਨੂੰ ਦਸਤਖਤ ਕੀਤੇ ਸਨ। ਇਹ ਇਬਾਰਤ ਉਸ ਦੀ ਕਬਰ ਉੱਤੇ ਦਰਜ ਏ।)

(ਸਦਾਅਤ ਹਸਨ ਮੰਟੋ ਨੇ ਆਪਣ ਕਤਬਾ ਲਿਖ ਕੇ 18 ਅਗਸਤ 1954 ਨੂੰ ਦਸਤਖਤ ਕੀਤੇ ਸਨ। ਇਹ ਇਬਾਰਤ ਉਸ ਦੀ ਕਬਰ ਉੱਤੇ ਦਰਜ ਏ।)

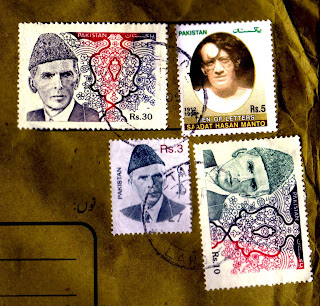

Photographs: Amarjit Chandan Collections

The article was first published at http://blog.hrisouthasian.org/2012/05/14/manto-my-garain/

PS: After reading the article Amarjit Chandan has told that Hamid Akhtar's ancestral village was Mehatpur near Nakodar. He passed away last year.

PS: After reading the article Amarjit Chandan has told that Hamid Akhtar's ancestral village was Mehatpur near Nakodar. He passed away last year.

very sensitive and moving account.

ReplyDelete